We’re living in an age with very little signposting to mark our journey from birth to death. Through the immense shifts in human life over the last few centuries we’ve become untethered from a continuous cultural thread that tells us how to behave and relate to one another through the different phases of life.

In most Indigenous cultures, some form of the following would happen to boys at the start of puberty: they’d be ceremonially snatched from their mothers by their fathers, taken out into the bush, and left alone there for some time. They’d sometimes be marked (often very painfully) with a physical token of the difficult experience they’d been through, like a scar or circumcision. These rites of passage served as signposts to say “this boy is now on the path to manhood, and he is to be treated differently henceforth.” He would have different rights and responsibilities compared to when he was a boy in his mother’s care.

For girls, there would be ceremonies and rituals to mark her first bleed which would affirm her womanhood and, again, signal a shift in rights and responsibilities henceforth.

It may not be a bad thing that we no longer practice or even know what our own cultures practiced in order to mark the passage from child to adult. Some of these practices could be quite traumatic and laden with heavy doses of shame, pride, and rigid definitions of masculinity and femininity. We have a lot more freedom nowadays. But freedom comes at a cost, and that is uncertainty and disconnection.

How do we know when we’re adults? In our culture, dominantly anglo-Australian, it’s heavily associated with the freedom to drink, to drive a car, and graduating from school. Great combo. There’s also getting our first paying job, having sex for the first time, and moving out of home (although this is happening later and later). But someone can do any of these things and still remain very childish, still putting responsibility for the consequences onto others. This results in a lot of wanton harm: from liver damage to car accidents, to unwanted and unsupported pregnancies, to share-house fights over who does the dishes. Becoming an adult is a tumultuous and very confusing time, and for most of us it takes the better part of ten or twelve years to figure out what maturity actually feels like. And we all know plenty of examples of boys in men’s bodies, who are still acting like kids in a sand pit, fighting over the yellow digger. Some of them run entire countries.

Not only are we confused about our own transition into adulthood, but sometimes those around us are, too. Many of us can imagine someone whose parents keep treating their children like they’re kids even when they’re 18 or 20. And plenty of people are drawn to leaders who appeal to their base tribal instincts like rival gangs wanting to play different games in the schoolyard.

What about weddings?

Getting married is another major life transition that comes with a slew of rights and responsibilities. It might even be the strongest remaining cultural institution many of us will participate in (although marriage rates are declining). But marriage and the wedding ceremony has also been eroded by our loss of cultural guide rails that tell us what we’re signing up for, and how others should relate to us in our new status. Divorce rates are higher than they’ve ever been: this alone suggests many of us do not know what we’re getting ourselves into, or don’t really consider the promises made in a wedding ceremony to be all that serious.

It’s a great thing that marriage has lost a lot of its baggage. Watch the documentary about Sinead O’Connor or the movie Philomena, and you’ll see what incredible harm was done to women in Ireland who had children outside of marriage. Or consider how many cultures accept polygamy (many wives for one husband) but never polyandry (many husbands for one wife) or expect the family of the bride to pay the groom’s family as though every woman and girl were a burden. Again, as in the case of rites of passage for young people, we’ve left behind plenty of harmful practices. And, as before, we can see that freedom is a double-edged sword. Do we want people to be trapped in bad relationships because marriage is regarded as a binding contract for life? Or do we want a wedding to be a meaningless party that can be upturned at any moment with a simple divorce?

In my opinion, freedom from strong cultural traditions is a good thing because it forces people to think for themselves and take their autonomy as individuals seriously. But autonomy as an individual comes with the responsibility to make clear and intentional choices about how to live.

Our culture, and our species, is in its adolescence: we grew up with rigid boundaries and cultures that told us exactly what to do. But we’re individuals with autonomy and strict cultural norms are oppressive to many while serving a few. So we threw them off and are wandering in the wilderness, and experiencing the mental health crisis, the divorce and single-parent rates and all-around lack of meaning that go along with that.

The structure we do need is one that reinforces our agency and puts us in a space of powerful presence in the moment. We need opportunities to be reminded that death comes to us all and each moment is precious, that life is not about being as comfortable or happy as possible but about creating things and relationships, facing our fears, and contributing to the wellbeing of others. How that looks can be different for each of us. We don’t need to be told a rigid story about what marriage is, or adulthood, or gender, or career or anything else. But we do need opportunities to recognise our own power and influence, to see that we’re constantly influencing the world around us for better or worse and that influence depends on our choices.

If that all seems a bit abstract, consider these questions:

Why are you getting married?

What does marriage mean to you?

What do you hope for your wedding to express?

What promises are you making?

Do you really believe in those promises?

What doubts or inner conflicts arise for you around marriage?

The Hero’s Journey

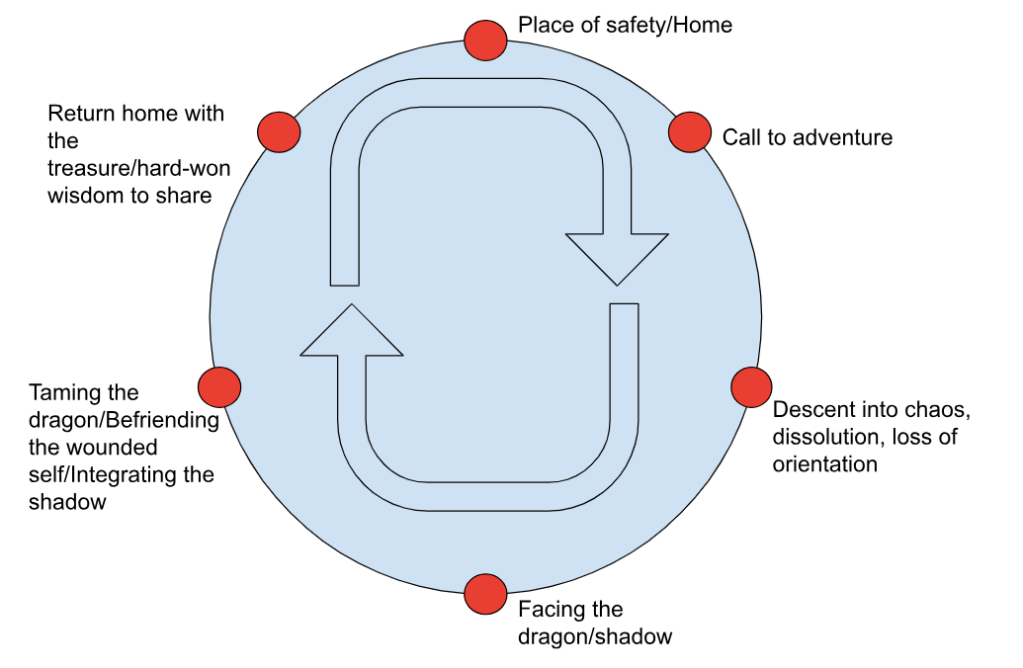

When it comes to the challenge of creating genuinely meaningful wedding ceremonies, one very important piece of the puzzle is the hero’s journey. Its most faithful proponent was a scholar and writer named Joseph Campbell, who poured his life into studying the myths and cultural traditions of the world, from the major world religions to the stories of ancient hunter gatherers. The hero’s journey is a map that charts everything from the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ to the trials and triumphs of Frodo Baggins and the thrill of one day seeing North Melbourne win the AFL premiership again. It also charts our own journeys through the most meaningful chapters of life. It places suffering and doubt in context and allows us to see how those periods of painful uncertainty or even the sense that all hope is lost are pivotal to the creation of wisdom, maturity and inner strength.

When the hero’s journey is spoken about it typically has about twelve steps but I’ve simplified it here for the application to a wedding ceremony. Despite all this grandiose talk about world history and the future of our species, I do believe simplicity is key!

A journey together in matrimony is both one big hero’s journey from beginning to end, and encapsulates a series of smaller cycles (courtship; moving in together; maybe having kids; parents ageing/dying; ageing/dying yourselves). A ceremony is an opportunity to embody that journey. By “embody” I mean it’s a chance to zoom out a little and see the journey for what it is, and also to play out the whole thing like a microcosm in the presence of your community.

A hero’s journey follows a cycle (please forgive the terrible Google Sheets graphic):

- So of course, before we met our future spouse we were single (sometimes maybe not but let’s assume so for the sake of simplicity). And being single is a kind of safety. We might feel lonely or horny or whatever but we basically get to do what we like, when we like, where we like, dreaming up big life plans and enjoying our freedom.

- Then we meet someone who really attracts us. At first it’s often a familiar sense of attraction we’ve felt before. But then it just gets deeper and deeper and we start wondering what the hell’s going on.

- We realise we don’t just like them. We love them. That’s scary, vulnerable and worrying. We wonder if our plans align. If our families will get along. Rarely is the journey of falling in love without its fears, doubts and anxieties.

- But we see the fears, doubts and anxieties for what they are and make a choice in favour of a higher vision of ourselves and our relationship. Through past relationships we’ve learnt the difference between trying hard to make things work and choosing to get out of our own way and let things work.

- As we realise that our doubts, fears and anxieties are actually just our own stories and have nothing to do with our partner, we learn to open up more and more in our relationship, to own our dysfunctional patterns and habits, to see clearly what we might have picked up in childhood or from things our parents said. And we start to smile at ourselves.

- Note: In many modern tales, the hero slays the beast/dragon/bad guy. But in many older ones the beast was actually befriended and tamed. I think this is a powerful reframing away from a hypermasculine stance of vanquishing and triumph and conflict and towards an integrated understanding that we’re our own best friend and worst enemy and no amount of forcefulness will help us.

- Through this whole journey we’ve grown and expanded and taken on wisdom. That wisdom often ends up being of service to others: to our partner, to friends or colleagues going through difficult relationships and to our children. We return from our journey with something beneficial to share.

A Wedding Ceremony as a Hero’s Journey

Thanks for sticking with me so far. Here’s the main point: any rite of passage, including a wedding ceremony, can follow the map of a hero’s journey. Too often, weddings stick to the lovey dovey stuff and neglect to really “go there” when it comes to the doubts and fears that falling in love and committing to another person entails. Weddings don’t need to be serious and solemn affairs, but paradoxically the party is enriched by the time we spend sitting with what’s uncomfortable or painful. Because then, when we erupt into celebration, we’re doing so knowing that we can rise above the shadow, and it’s not left there lurking in the corner while we try our best to turn a blind eye.

When I work with couples to craft a wedding ceremony, I help them create moments where they can embody each of these stages:

- The safety and ease before they got together

- The wild and intoxicating ride of falling in love

- The fear and doubts that spring up as they feel their control slipping

- The choices that come from the heart as they decide to spend their lives together

- The deep joy and wisdom that emanates out into every other relationship and endeavour from the journey that their relationship has been on and continues on

Where to now?

If you like what you’ve read here and you’re planning a wedding ceremony of your own, get in touch and we can start the process. Even if you’re not planning a wedding, but you liked reading this, get in touch anyway!

I hope this has helped to ignite you in some way to think about your life and the journey you’re on, or maybe to have some transformative conversations with important people in your life.

Beyond my work as a celebrant my life’s pleasure is in elevating people, organisations and businesses (which are just collections of people!) towards their highest aspirations. If you’re in business or run a community organisation, I would love to consult with you on how you can incorporate creative structures like the hero’s journey into your practice and find new layers of depth and meaning in what you do.

Aristotle is famous for saying “the unexamined life is not worth living.” I’ve typically assumed that to be quite a serious undertaking: examination to me speaks of frowning scientists behind microscopes, or stiff backed invigilators prowling halls of silently pen-scratching students. But to examine our lives also means to see the moments of celebration, the sparks of joy, and the irrepressible creative intelligence that flows through us and erupts, daily, in smiles, laughter and twinkling eyes.

Leave a comment